A new federal copyright tribunal launched in 2022. Stanford Law students analyzed over 1,000 cases. Learn who is using the CCB, why dismissals dominate, and how creators might better navigate the system.

In 2020, Congress passed the CASE Act calling for the creation of a new copyright tribunal—the Copyright Claims Board (CCB). The CCB was launched by June 2022, giving creators a new forum where they could assert their copyright claims. This tribunal was designed to be affordable, fully online, and simplified compared to its analog in federal court. The CCB also maintains a public docket of its cases, inviting analysis into its trajectory so far. It’s rare to witness the development of a new forum live and actually have the information to explore how it has been working. As students in the Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic at Stanford Law School, we scraped the CCB’s data with several research questions in mind.

Within the first year of the CCB’s launch, the data revealed that few cases reached final determinations and over 70% of claims were dismissed. We were curious about why this was, and whether this still held true after a few years. Which creators filed claims with the CCB? Were there clear patterns in the effect of representation on case outcomes? What were the reasons claims were dismissed, and could creators use this information to prepare claims that are likely to succeed in the future? Guided by questions about who the CCB serves and why, we investigated cases in the CCB’s docket from its start in June 2022 through January 1, 2025. Our findings are summarized below.

Few Cases Reach Final Determinations

- Of more than 1,000 cases in CCB’s docket, only 18 cases, or 1.8%, reached a final determination. To reach this stage, a case must be properly filed, clear the CCB’s compliance review, meet service requirements, and of course, reach a determination on the merits of the case. Some cases are dismissed before this point for several reasons, which we will cover later.

- A number of repeat claimants reached final determinations in at least one of their claims. Julie Dermansky, Joe Hand Promotions, and Michelle Shocked have each filed more than 10 claims with the CCB and each has reached a final determination for at least one of their claims.

- Among final determinations where the claimant prevailed, the damages awarded ranged from $1,200 to $7,000.

- Claimants and respondents in cases that reached final determination varied and ranged from individuals to well-known corporations. Claimants also sought to enforce protections of several types of works, including songs, photographs, university assignments and paper prompts, novels, videos and more.

- It is unclear whether certain types of claims, claimants, or works are more likely to reach final determination than others. However, what is clear is that the chances of getting to this stage have been slim, even for those who are more experienced with the CCB’s process.

The Majority of Cases are Dismissed

- Dismissal is the modal outcome for cases filed with the CCB, though dismissal can occur at several stages in a proceeding. As these dismissals are most often without prejudice, parties can still re-file their claims after dismissal if they choose to.

- The most common reason for dismissal is failure to timely or properly amend a complaint. This happens when a complaint does not meet the CCB’s requirements during early screening. After claimants file their claims, the CCB reviews them (in a phase called “Compliance Review”) to surface issues. The CCB alerts claimants of these issues and asks claimants to amend their complaint within a given period of time to fix them. These issues vary, but include missing information in the claim, failure to pay fees, missing copyright registration (when required), use of the claims process against someone who does not reside in the US, or use of the CCB for claims the tribunal cannot preside over (e.g. contract disputes related to copyright licensing). Sometimes, parties did not file amended claims at all after being notified of issues, resulting in dismissal. In other cases, claimants did amend their claims, but those amended claims still did not pass compliance review after two rounds of amendments. If the amended claim still presents issues after the second opportunity to amend, the CCB will dismiss it.

- The second-most common reason for dismissal involves issues with providing service, including failure to file proof of service and ineffective service. While the CCB’s proceedings are relatively streamlined and simplified, rules of service come from a different authority: the respondent’s applicable state law. Service can be more difficult to navigate than other stages of a CCB proceeding for this reason, and the service rules can vary by state.

- Close behind is dismissal because the respondent opted out of the case. It may seem unsurprising that a respondent would choose to opt out of a case, however, claimants are also able to drop out which was the fourth common category of dismissal types. These trends in dismissals stayed relatively stable across 2022-2024. While it is not possible to tell why claimants request to dismiss their own cases, it may be the result of settlements the parties have reached outside the CCB or their choice to use federal courts to resolve the issue instead.

Demographics and Dismissals

- Effect of Representation. Most cases that were not dismissed involved a claimant and a respondent who were both not represented by counsel. It is not clear that claimants are more likely to be successful in reaching a final determination if they retain counsel.

- Status of Party. Of the cases that were dismissed, it was more likely that both parties were individuals. In general, the majority of claimants and the majority of respondents are individuals—significantly fewer are corporations, LLCs or other entities (e.g. nonprofits or government entities).

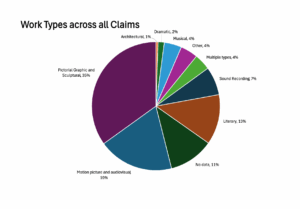

- Work Types. Of the cases that were dismissed, most claims involved pictorial graphic and sculptural works. The chart below shows the demographic breakdown of work types across claims that were dismissed. The highest number of dismissals involved claims for pictorial graphic and sculptural works. However, the percentage rate for dismissals of claims involving musical work types (94%) was higher.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

Claimants and Respondents

With the data that was collected, we were able to see where claimants were actually located, and we found that most domestic claimants were located in California. New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Florida also had a large number of claimants. Outside of the US, the top countries represented were the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Germany, and Canada.

Some parties appeared in front of the CCB as a claimant in one case and later again as a respondent in a different, unrelated case. There were some parties, for example, who were respondents in a claim in 2022, and then appeared as claimants in 2023 or 2024. There have been a handful of claimants who have brought more than 10 claims to the CCB in the past couple of years, and similarly there have been a handful of respondents involved in more than 10 cases in front of the CCB in the past couple of years.

A large number of these repeating respondents are platforms such as YouTube, Amazon, and Etsy. In these cases, the claimant was generally not represented by counsel, and every case against a content service provider was dismissed. Still, the fact that these claims were dismissed does not necessarily mean that the claimant was unsuccessful. Some claimants brought claims against a platform to have someone else’s infringing content, which was hosted on the platform, taken down. Claimants can only bring a claim against an online service provider if it loses its safe harbor under Section 512 of the Copyright Act. Online service providers gain a safe harbor by providing a platform for handling takedown notices and handling requests in a timely manner, as outlined by Section 512. If a claimant files a takedown notice with a platform for potentially infringing material on the platform, the alleged infringer can file a counter notice. The online service provider may choose to reinstate the content while waiting for the claimant to bring formal legal action. It is usually in these situations where a claimant brings an erroneous claim against the platform as opposed to the infringing author. The CCB has no obligation to a claimant who brings a misrepresentation claim against a platform if the platform still has safe harbor—the actual conflict is between the author of the infringing content and the claimant. In addition, even if the platform lost its safe harbor, it can still choose to opt out of the CCB proceeding.

Authors

-

Juelsgaard Clinic Member, Stanford J.D Candidate, 2025

February 9, 2024

Photo by Christine BakerResearched and written under the guidance of Phil Malone, Director of Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic, Mills Legal Clinic, Stanford Law School, and Nina Srejovic, Clinical Supervising Attorney and Lecturer, Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic

-

Stanford Law School Mills Legal Clinic on February 28th 2025.

Photography by: Christine BakerResearched and written under the guidance of Phil Malone, Director of Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic, Mills Legal Clinic, Stanford Law School, and Nina Srejovic, Clinical Supervising Attorney and Lecturer, Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic