Reenvisioning Retirement: A Spectrum of Interventions and Community Care

Why a Toolkit?

When we think about all of the ways we are invested in our communities, we often don’t think about our retirement savings. Yet, the total amount of retirement assets in the United States is about $44.1 trillion and accounts for 34% of all household assets. Of that, $12.4 trillion is currently invested in “defined contribution” plans—think your 401(k) or 403(b)—and $8.9 trillion in government “defined benefit” plans (i.e., public pensions). That is a lot of money! However, who gets to participate in our retirement systems, how decisions are made about our retirement money, and how that money is used before we retire is often complex, and frankly, hard to navigate in a way that is aligned with our values.

Traditional retirement funds often include funds from corporations that are harming vulnerable populations. Even funds that are supposed to be less harmful often still hold funds from corporations that have a negative impact on communities. So, what are the alternatives for someone who wants to align their retirement investments with values that center thriving communities and ecosystems? And what are some interventions to consider at the tactical, organizational, and worker level? This toolkit explores these questions along a spectrum of care.

Who is this Toolkit For?

This toolkit is meant to support individuals, organizations, foundations, policymakers, and values-aligned financial professionals in reenvisioning the retirement landscape.

Why Should We Care about Our Retirement Funds?

Our retirement savings make up a large percentage of the economic puzzle in the U.S., and there is tremendous potential to reenvision how we think about these resources:

Who gets to participate?

The amount of wealth held in traditional retirement savings systems is staggering—yet, not everyone has access to that wealth. Among the lowest third of earners who have retirement savings in the United States, white people have 345% more savings than their Black counterparts. Only 49% of Black women have retirement savings, compared to 62% of the overall population (this is inclusive of all assets, like a home). This disparity is due, in large part, to well-documented systemic inequities in wealth and income that have compounding effects in retirement. Disparities in worker pay, unemployment, access to benefits, intergenerational wealth, asset ownership, savings, and other factors over a lifetime affect if and how much a worker can save for retirement.

Who makes decisions?

Our retirement savings investments? are largely out of our hands. For the majority of those who do have retirement savings, that money is invested in either a defined contribution plan or a defined benefit plan. We might get to decide how much to contribute to this plan, and might even have the ability to pick certain pooled funds the plan is invested in, but that is where investor choice at traditional financial institutions begins and ends. For the curious investor, it can also be difficult to learn where these pooled funds are actually invested, and once you do, you may be surprised to learn what companies your retirement funds are supporting!

What is this Resource?

This guide offers some creative and unconventional ways that employers, workers, and values-aligned fund managers might leverage retirement savings to benefit communities. The toolkit explores how we might reenvision retirement along a spectrum of interventions and community care: from harm reduction to divesting from traditional financial structures altogether. We invite you to reenvision retirement investing as rooted in a model based on solidarity and community care by considering these interventions at the tactical, organizational, and worker levels:

Next Steps: Resources and a Community of Practice

October 30th: Webinar “Putting Your Money Where Your Mission Is: Philanthropic Strategies for Divestment and Impact Investing” hosted by Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees. Register Here.

Download the Toolkit HERE

Explore Early Insights from the Copyright Claims Board (CCB)

A new federal copyright tribunal launched in 2022. Stanford Law students analyzed over 1,000 cases. Learn who is using the CCB, why dismissals dominate, and how creators might better navigate the system.

In 2020, Congress passed the CASE Act calling for the creation of a new copyright tribunal—the Copyright Claims Board (CCB). The CCB was launched by June 2022, giving creators a new forum where they could assert their copyright claims. This tribunal was designed to be affordable, fully online, and simplified compared to its analog in federal court. The CCB also maintains a public docket of its cases, inviting analysis into its trajectory so far. It’s rare to witness the development of a new forum live and actually have the information to explore how it has been working. As students in the Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic at Stanford Law School, we scraped the CCB’s data with several research questions in mind.

Within the first year of the CCB’s launch, the data revealed that few cases reached final determinations and over 70% of claims were dismissed. We were curious about why this was, and whether this still held true after a few years. Which creators filed claims with the CCB? Were there clear patterns in the effect of representation on case outcomes? What were the reasons claims were dismissed, and could creators use this information to prepare claims that are likely to succeed in the future? Guided by questions about who the CCB serves and why, we investigated cases in the CCB’s docket from its start in June 2022 through January 1, 2025. Our findings are summarized below.

Few Cases Reach Final Determinations

- Of more than 1,000 cases in CCB’s docket, only 18 cases, or 1.8%, reached a final determination. To reach this stage, a case must be properly filed, clear the CCB’s compliance review, meet service requirements, and of course, reach a determination on the merits of the case. Some cases are dismissed before this point for several reasons, which we will cover later.

- A number of repeat claimants reached final determinations in at least one of their claims. Julie Dermansky, Joe Hand Promotions, and Michelle Shocked have each filed more than 10 claims with the CCB and each has reached a final determination for at least one of their claims.

- Among final determinations where the claimant prevailed, the damages awarded ranged from $1,200 to $7,000.

- Claimants and respondents in cases that reached final determination varied and ranged from individuals to well-known corporations. Claimants also sought to enforce protections of several types of works, including songs, photographs, university assignments and paper prompts, novels, videos and more.

- It is unclear whether certain types of claims, claimants, or works are more likely to reach final determination than others. However, what is clear is that the chances of getting to this stage have been slim, even for those who are more experienced with the CCB’s process.

The Majority of Cases are Dismissed

- Dismissal is the modal outcome for cases filed with the CCB, though dismissal can occur at several stages in a proceeding. As these dismissals are most often without prejudice, parties can still re-file their claims after dismissal if they choose to.

- The most common reason for dismissal is failure to timely or properly amend a complaint. This happens when a complaint does not meet the CCB’s requirements during early screening. After claimants file their claims, the CCB reviews them (in a phase called “Compliance Review”) to surface issues. The CCB alerts claimants of these issues and asks claimants to amend their complaint within a given period of time to fix them. These issues vary, but include missing information in the claim, failure to pay fees, missing copyright registration (when required), use of the claims process against someone who does not reside in the US, or use of the CCB for claims the tribunal cannot preside over (e.g. contract disputes related to copyright licensing). Sometimes, parties did not file amended claims at all after being notified of issues, resulting in dismissal. In other cases, claimants did amend their claims, but those amended claims still did not pass compliance review after two rounds of amendments. If the amended claim still presents issues after the second opportunity to amend, the CCB will dismiss it.

- The second-most common reason for dismissal involves issues with providing service, including failure to file proof of service and ineffective service. While the CCB’s proceedings are relatively streamlined and simplified, rules of service come from a different authority: the respondent’s applicable state law. Service can be more difficult to navigate than other stages of a CCB proceeding for this reason, and the service rules can vary by state.

- Close behind is dismissal because the respondent opted out of the case. It may seem unsurprising that a respondent would choose to opt out of a case, however, claimants are also able to drop out which was the fourth common category of dismissal types. These trends in dismissals stayed relatively stable across 2022-2024. While it is not possible to tell why claimants request to dismiss their own cases, it may be the result of settlements the parties have reached outside the CCB or their choice to use federal courts to resolve the issue instead.

Demographics and Dismissals

- Effect of Representation. Most cases that were not dismissed involved a claimant and a respondent who were both not represented by counsel. It is not clear that claimants are more likely to be successful in reaching a final determination if they retain counsel.

- Status of Party. Of the cases that were dismissed, it was more likely that both parties were individuals. In general, the majority of claimants and the majority of respondents are individuals—significantly fewer are corporations, LLCs or other entities (e.g. nonprofits or government entities).

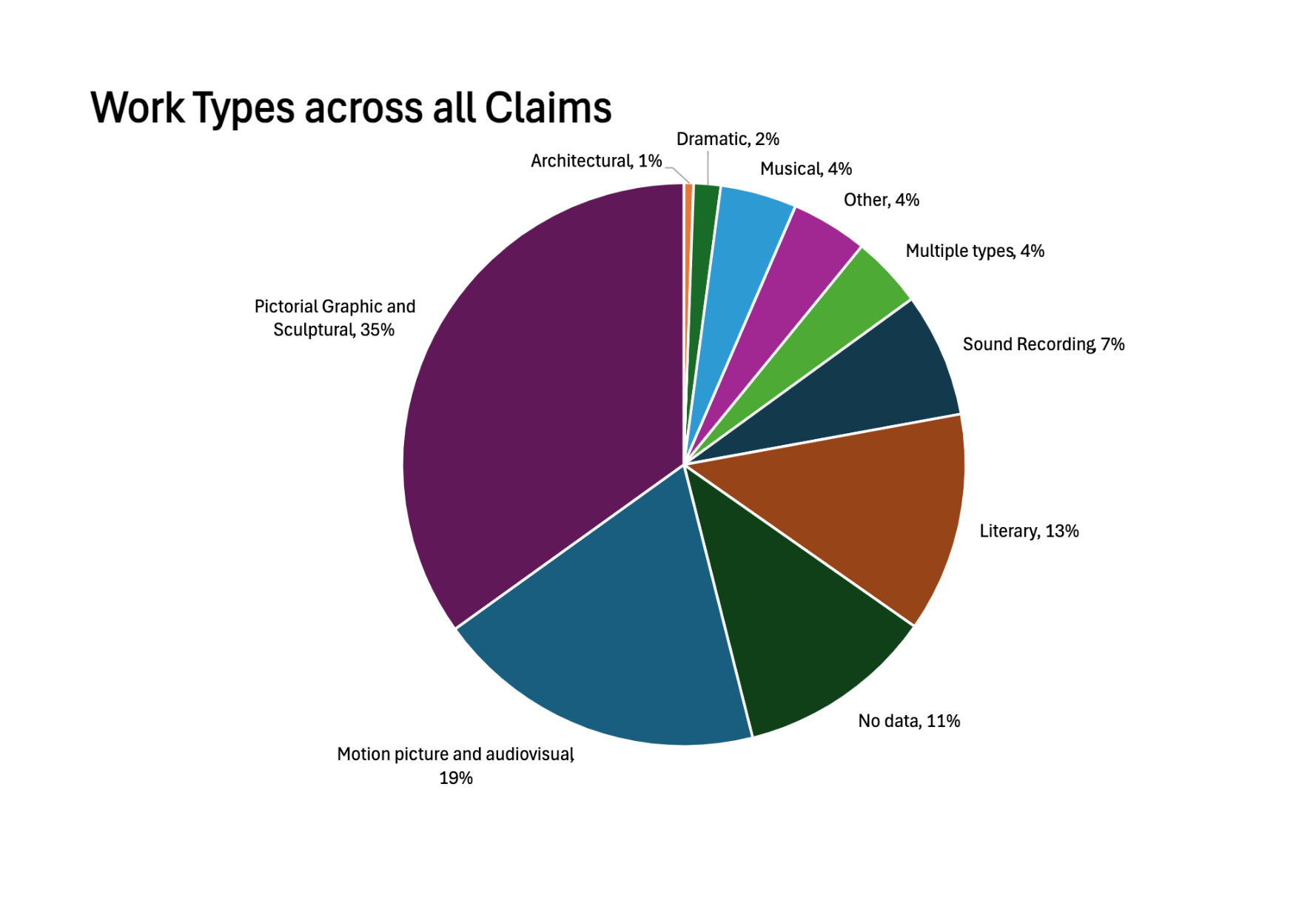

- Work Types. Of the cases that were dismissed, most claims involved pictorial graphic and sculptural works. The chart below shows the demographic breakdown of work types across claims that were dismissed. The highest number of dismissals involved claims for pictorial graphic and sculptural works. However, the percentage rate for dismissals of claims involving musical work types (94%) was higher.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

Claimants and Respondents

With the data that was collected, we were able to see where claimants were actually located, and we found that most domestic claimants were located in California. New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Florida also had a large number of claimants. Outside of the US, the top countries represented were the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Germany, and Canada.

Some parties appeared in front of the CCB as a claimant in one case and later again as a respondent in a different, unrelated case. There were some parties, for example, who were respondents in a claim in 2022, and then appeared as claimants in 2023 or 2024. There have been a handful of claimants who have brought more than 10 claims to the CCB in the past couple of years, and similarly there have been a handful of respondents involved in more than 10 cases in front of the CCB in the past couple of years.

A large number of these repeating respondents are platforms such as YouTube, Amazon, and Etsy. In these cases, the claimant was generally not represented by counsel, and every case against a content service provider was dismissed. Still, the fact that these claims were dismissed does not necessarily mean that the claimant was unsuccessful. Some claimants brought claims against a platform to have someone else’s infringing content, which was hosted on the platform, taken down. Claimants can only bring a claim against an online service provider if it loses its safe harbor under Section 512 of the Copyright Act. Online service providers gain a safe harbor by providing a platform for handling takedown notices and handling requests in a timely manner, as outlined by Section 512. If a claimant files a takedown notice with a platform for potentially infringing material on the platform, the alleged infringer can file a counter notice. The online service provider may choose to reinstate the content while waiting for the claimant to bring formal legal action. It is usually in these situations where a claimant brings an erroneous claim against the platform as opposed to the infringing author. The CCB has no obligation to a claimant who brings a misrepresentation claim against a platform if the platform still has safe harbor—the actual conflict is between the author of the infringing content and the claimant. In addition, even if the platform lost its safe harbor, it can still choose to opt out of the CCB proceeding.

Tracking Federal Legislation on Gig Work and Web3

There is plenty of turmoil to go around in Washington, DC these days. CCI is not immune to such turbulence. And at the same time, our work at the edge of arts, culture, safety nets and technology give us the visibility to see the opportunities embedded in the current moment. They do exist! For this reason, while CCI does not at present engage in policy and advocacy, we are tracking federal legislation that affects our priorities of individual and community self-determination. Below, I have highlighted four legislative items: two pertaining to gig worker safety nets (one that passed and one that is still pending) and two pertaining to cryptocurrency regulation (one that passed and one still pending), which may affect the many artists who use or engage with Web3 technologies to sell work and collectivize power.

GIG WORKER SAFETY NET LEGISLATION

PASSED: One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Bill. We were surprised to see the inclusion of so-called Trump Baby Bonds in the final legislation. It’s curious that a provision long pushed by progressives in the guaranteed income space was included in OBBBA, though in practice these baby bonds are far from the original vision. The “baby bonds” in the final bill are largely similar to retirement savings accounts (vs. some sort of child savings support) – but differ in that U.S. citizens with Social Security numbers born between 2025 and 2029 will get an investment of $1k by the Federal government in their accounts. The bill is scant on details, and it is likely that most accounts will be held by mainstream financial institutions and administered by the Treasury Dept.

PENDING: GOP Portable Benefits proposals. Sen Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and other members introduced several bills around independent workers. Cassidy’s attempts to separate benefits provision from the federal definition of “employee.” It would allow employers to provide benefits to their 1099 contractors without fear of federal prosecution for misclassification. A press release on the bills is here. Similar legislation has either been passed or is moving through statehouses in red and blue states (UT, TN and AL have enacted laws; AK, FL, NV and NJ have proposed laws). It is unlikely that any action will take place in this Congress, none is scheduled in the Senate as of now. The House Education Committee did markup a similar house version to the Scott Modern Worker Empowerment Act (essentially a classification text for federal law).

CRYPTO CURRENCY LEGISLATION:

PASSED: GENIUS Act, passed into law in July. It is an extremely specific bill that passed with bipartisan support. In essence, the bill established a federal framework for issuing and trading stablecoins (crypto assets usually pegged to the US dollar). This bill also allows traditional finance entities (banks, major retailers, and others) to enter the crypto market. The bill was relatively narrow in scope, leaving broader market structuring and overall regulation to the CLARITY Act, which has yet to pass both houses.

PENDING: CLARITY Act or the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act. The House passed its version in July. The Senate is currently working on its version, called RFIA (Responsible Financial Innovation Act). It is less likely to pass than the GENIUS Act, because it is far more comprehensive. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who was opposed to the GENIUS Act, has been far more vocal in her opposition to the more CLARITY Act in an effort to peel Senate Dems away from support of the bill. The bill would amend the Securities Act of 1933 to exempt most crypto assets from the definition of “securities” and thus regulation by the SEC. If passed, the CLARITY Act would constitute the first time in its history that the Securities Act would be amended to exempt (rather than include) an asset from the definition of a security, and could result in other securities industries seeking exemption from oversight. Leaders in Decentralized Finance or DeFi are quietly opposed to the bill. Seven Dems are needed to vote with Republicans on the Senate’s version of the bill to get it through the next step in the legislative process. Republicans hope to do so by the end of August, but the numbers are not in their favor.

Arts Worker Supports Issue Brief

Arts Worker Supports - Issue Brief

A summary of the public policies needed to build economic security for arts workers and microbusinesses

We worked with arts advocates to define a policy agenda that supports arts workers and microbusinesses.

In Spring/Summer of 2023, we worked with a voluntary group of arts worker advocates through the Cultural Advocacy Group to identify a set of policies needed to support the economic security of arts workers and microbusinesses. This issue brief is the result of our collective effort.

The brief summarizes the challenges people working in the arts face to access social protections, both as independent workers and microbusinesses, and outlines a series of policy reforms needed to build a safety net for all.

The brief is meant to be a resource for the field, so please feel free to use it in your own advocacy!