Reflections from the Platform Cooperativism Conference in Istanbul

This story was originally published on Subvert’s blog https://subvert.fm/blog/reflections-from-the-platform-cooperativism-conference-in-istanbul/ on January 21, 2026

For those of you who don’t know, Subvert is part of a small corner of the tech world called “Platform Cooperatives”. The idea is that there are many different kinds of cooperatives: worker cooperatives, producer cooperatives, retail cooperatives, etc. So what do we call online cooperatives, or internet infrastructure owned as a co-op? Platform co-ops.

This small subculture within tech often goes unnoticed in mainstream tech culture. It’s organized around simple questions. What if platforms were owned and controlled by the communities that rely on them instead of founders and investors? Could there be an Uber owned by drivers? An OnlyFans owned by sex workers? Or in the case of Subvert – could there be a Bandcamp owned by its artists and community?

Since 2015, this community has been convening at annual conferences organized by the Platform Cooperativism Consortium. This organization, led by Trebor Scholz, professor at The New School and longtime advocate for worker-owned digital platforms, has held a global focus, hosting these gatherings across the globe: in New York City, Hong Kong, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, India, Kenya, and now Istanbul.

Subvert traveled to Istanbul and attended as part of a panel, with our trip generously sponsored by the Center for Cultural Innovation – the same non-profit organization that supported our early work, including a fellowship that helped us design and print our first zine run.

These conferences have always centered discussion on how digital platforms can be owned and governed by the people who use and depend on them. But this year felt different. As the world is consumed with AI hype, this conference turned its focus to the intersection of artificial intelligence and online cooperativism.

Why AI and co-ops?

Before getting into what was discussed, it’s worth naming where many of us in the Subvert community stand on AI: skeptical at best, hostile at worst.

Generative AI music is widely considered slop. Bandcamp recently introduced a policy which bans AI-generated music. And the news keeps surfacing examples of AI companies like Suno training models by scraping copyrighted work without consent or compensation. Within music, the conversations about AI are particularly hostile. So where do the conversations around AI and cooperatives intersect?

We came with an open mind to hear from academic researchers and practitioners alike what they see in this intersection.

The Solidarity Stack

Trebor Scholz opened the conference by introducing what he calls the “Solidarity Stack” – a framework he developed with researcher Morshed Mannan for thinking about cooperative ownership across the entire AI supply chain.

“The AI crisis won’t be solved by laws or better code alone. It will be solved by people—by you—organizing across layers, borders, and disciplines. Across the stack.” – Trebor Scholz

The core idea he presented is that AI isn’t something that just exists at the code level. AI systems are produced by many layers: rare earth mineral mining for chips, data centers, human labor, data collections, algorithms, models, and apps. What Trebor outlined is a vision where each of these steps can be run as cooperatives, rather than controlled by a small number of corporations.

The Solidarity Stack asks: what if each of these layers could be cooperatively owned? What if there were cooperative mines, community-owned data centers, worker-owned AI development shops, and democratically governed applications?

It’s an ambitious, broad vision. And the realization of this vision feels distant and hopeful – bordering on impossible. But Trebor’s framework provides a useful map for seeing where intervention might be possible, and where the cooperative movement is already experimenting.

The hidden labor of AI

The conference opened with a screening of In the Belly of AI, a documentary directed by Henri Poulain and co-written by sociologist Antonio Casilli. The film traces the invisible human labor that powers AI systems: the data annotators, content moderators, and ghost workers scattered across the Global South who train models for a few dollars a day.

The movie illustrated that none of these AI models exist without exploited human labor.

“It depends on who owns it”

It was interesting that at this event, there was less overt dismissal of AI than we commonly see within Subvert’s membership. These researchers and practitioners shared a view that the root problem of AI exists within its capitalist business models, and less so within the technology

Transkribus, an AI tool for transcribing handwritten historical documents, must be one of the most successful cooperative platforms today. The platform has over 300,000 registered users, has processed more than 100 million pages of historical documents, and is co-owned by 237 members from 35 countries. It even won the European Union’s Horizon Impact Award in 2020.

Transkribus got started within academic research projects funded by the European Commission to read handwritten texts. The research that created this tool became valuable and useful enough that people around the world wanted to use it, and a community and business formed around it. When the EU funding ended in 2019, they transitioned into a cooperative rather than selling to a larger company.

Melissa Terras, a professor at the University of Edinburgh and director of its Centre for Digital Scholarship, spoke about how the cooperative has operated for years, resisting acquisition offers and maintaining democratic governance.

Professor Terras had this to say about AI:

“AI is just lines of code. It depends on what we point it at and who owns it.”

Her argument is that the problem isn’t the technology – it’s the business models. Cooperative structures are alternatives to extractive business logic.

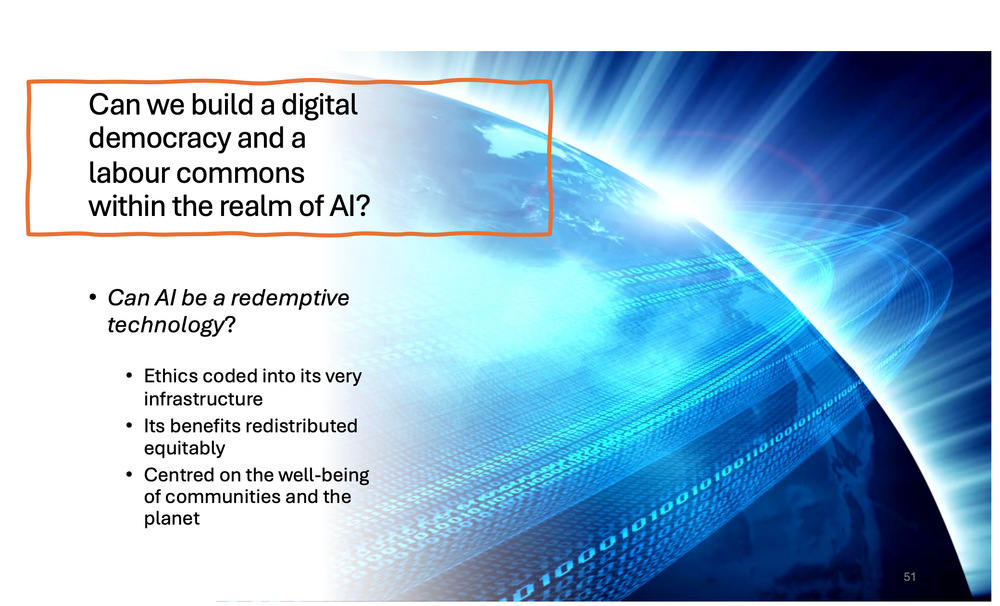

AI optimism: can it be a “labor commons”?

Marcelo Vieta, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies worker cooperatives and self-management, offered the most optimistic talk of the conference. He said,

“We built these systems. We can redirect them. Or slow them down and re-design them.”

Vieta suggested that AI can become part of a “labor commons” – allowing AI, data, and algorithms to be shared resources collectively governed by workers, instead of commodities extracted for profit. He pointed to The Drivers Cooperative in New York as an example: the tech is similar to Lyft and Uber, but the ownership and governance are entirely different.

His point wasn’t that we should seize existing AI infrastructure. It was that we can build alternatives from the ground up. Or as he put it:

“recoding architectures, data practices, and incentive structures around human scale and ecological limits.”

He asks:

Can AI be a redemptive technology?

However, it’s worth noting that when an audience member inquired whether any architects of the dominant AI systems were in the room, they weren’t. To me, some of the optimism was dampened by this feeling that a group of researchers and academics were raging against the machine halfway across the world from San Francisco, while the AI architects we were raging against were neither present nor aware that this conversation was happening.

Cooperatives in practice

I shared my panel with Stuart Fulton, who runs PescaData, a data platform used by small-scale fishing cooperatives in Mexico to share information with each other. PescaData is worlds away from the traditional Silicon Valley tech world, so it’s refreshing to see smaller scale platforms from Latin America be represented. I appreciate the curation of Trebor Scholz, who has continued to extend a global lens to these events, making sure not to create a US-centric echo chamber of discourse.

Hypha Worker Co-op, based in Toronto, presented RooLLM. Roo is the name they gave their own internal, self-hosted AI tool which helps the workers within their cooperative coordinate by making internal company data and insights more accessible, and even support their own governance. It’s a small but real example of what it might look like for a cooperative to run AI infrastructure on its own terms. No reliance on OpenAI or Google. And no replacing jobs. Just experimenting with ways to empower worker-owners within a co-op.

Felix Weth, CEO of Platform21, made the case for cooperatives to invest in building shared compute infrastructure. He argued that without access to processing power, cooperative AI will always be dependent on the very corporations it hopes to challenge. His call to action: build the world’s largest collectively owned compute cluster.

Research vs Practice

In a world of very well-placed tech cynicism, there is something nice about being in a room with optimistic and hopeful tech nerds. I first attended a Platform Cooperativism Conference in 2019, in New York City. Back then, there was an energy that I found to be contagious. The people there wanted to build cooperative replacements for Facebook, Google, everything. The optimism was real.

Six years later, some things have changed. It’s true that platform cooperatives have made progress, but the ambition of the early days has dampened. Transkribus shows that there are real successful examples in practice today. That’s real progress. Still, I couldn’t help but feel some disappointment by the imbalance of the discourse.

There weren’t enough practitioners centered in the discussions I heard. Researchers and academics far outnumbered people who had actually started or were running cooperatives. The conversations often felt like observing rather than participating. There were more people studying the possibilities of a movement rather than picking up a shovel.

This isn’t necessarily the fault of the conference organizers. The Platform Cooperativism Consortium has roots as an academic organization, after all. But if the cooperative movement is going to matter in the AI era, the discourse needs to be reclaimed by people in the arena.

I have always felt that the health and success of the platform cooperativism movement is contingent on moving it away from the world of dry academic PDFs and research – and bringing the ideas to life through real, successful, consumer tech applications. But the space is largely still firmly planted in academia.

Whenever I am at a platform cooperative event, I can’t help but compare it to traditional tech events like TechCrunch Disrupt, where founders, funders, and journalists are centered in conversation. Say what you want about the traditional tech world – it’s organized around people building things. And I think the cooperative movement needs more of that energy. More praxis to balance the theory.

Maybe the answer is for practitioners like Subvert to organize our own convenings, bringing together the people actually running cooperatives and creating space for the conversations we need to have. Less theory, and more practical examples of artists joining together to create their own worlds and systems.

Continued Work

Despite my critiques, there was something energizing about being in a room with people from thirty countries, all trying to figure out how to build something different.

One of the things that I loved was hearing genuine enthusiasm from many of the conference participants about what Subvert is doing. It was a reminder of the potential for impact we can have – through demonstrating our ability to be commercially successful against a legacy incumbent.

And it’s also a reminder that there is room for developing our own positioning on AI as it relates to our cooperative. This is an invitation for everyone reading this: we’re currently co-creating our own AI policy in the Subvert forum. If you haven’t weighed in yet, now’s a good time.

The questions raised in Istanbul about who owns and controls AI mirror Subvert’s questions about who owns and controls music platforms. These questions will only become louder. And the answers will be shaped by those who get in the arena and participate.

Reenvisioning Retirement: A Spectrum of Interventions and Community Care

Why a Toolkit?

When we think about all of the ways we are invested in our communities, we often don’t think about our retirement savings. Yet, the total amount of retirement assets in the United States is about $44.1 trillion and accounts for 34% of all household assets. Of that, $12.4 trillion is currently invested in “defined contribution” plans—think your 401(k) or 403(b)—and $8.9 trillion in government “defined benefit” plans (i.e., public pensions). That is a lot of money! However, who gets to participate in our retirement systems, how decisions are made about our retirement money, and how that money is used before we retire is often complex, and frankly, hard to navigate in a way that is aligned with our values.

Traditional retirement funds often include funds from corporations that are harming vulnerable populations. Even funds that are supposed to be less harmful often still hold funds from corporations that have a negative impact on communities. So, what are the alternatives for someone who wants to align their retirement investments with values that center thriving communities and ecosystems? And what are some interventions to consider at the tactical, organizational, and worker level? This toolkit explores these questions along a spectrum of care.

Who is this Toolkit For?

This toolkit is meant to support individuals, organizations, foundations, policymakers, and values-aligned financial professionals in reenvisioning the retirement landscape.

Why Should We Care about Our Retirement Funds?

Our retirement savings make up a large percentage of the economic puzzle in the U.S., and there is tremendous potential to reenvision how we think about these resources:

Who gets to participate?

The amount of wealth held in traditional retirement savings systems is staggering—yet, not everyone has access to that wealth. Among the lowest third of earners who have retirement savings in the United States, white people have 345% more savings than their Black counterparts. Only 49% of Black women have retirement savings, compared to 62% of the overall population (this is inclusive of all assets, like a home). This disparity is due, in large part, to well-documented systemic inequities in wealth and income that have compounding effects in retirement. Disparities in worker pay, unemployment, access to benefits, intergenerational wealth, asset ownership, savings, and other factors over a lifetime affect if and how much a worker can save for retirement.

Who makes decisions?

Our retirement savings investments? are largely out of our hands. For the majority of those who do have retirement savings, that money is invested in either a defined contribution plan or a defined benefit plan. We might get to decide how much to contribute to this plan, and might even have the ability to pick certain pooled funds the plan is invested in, but that is where investor choice at traditional financial institutions begins and ends. For the curious investor, it can also be difficult to learn where these pooled funds are actually invested, and once you do, you may be surprised to learn what companies your retirement funds are supporting!

What is this Resource?

This guide offers some creative and unconventional ways that employers, workers, and values-aligned fund managers might leverage retirement savings to benefit communities. The toolkit explores how we might reenvision retirement along a spectrum of interventions and community care: from harm reduction to divesting from traditional financial structures altogether. We invite you to reenvision retirement investing as rooted in a model based on solidarity and community care by considering these interventions at the tactical, organizational, and worker levels:

Next Steps: Resources and a Community of Practice

October 30th: Webinar “Putting Your Money Where Your Mission Is: Philanthropic Strategies for Divestment and Impact Investing” hosted by Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees. Register Here.

Download the Toolkit HERE

Explore Early Insights from the Copyright Claims Board (CCB)

A new federal copyright tribunal launched in 2022. Stanford Law students analyzed over 1,000 cases. Learn who is using the CCB, why dismissals dominate, and how creators might better navigate the system.

In 2020, Congress passed the CASE Act calling for the creation of a new copyright tribunal—the Copyright Claims Board (CCB). The CCB was launched by June 2022, giving creators a new forum where they could assert their copyright claims. This tribunal was designed to be affordable, fully online, and simplified compared to its analog in federal court. The CCB also maintains a public docket of its cases, inviting analysis into its trajectory so far. It’s rare to witness the development of a new forum live and actually have the information to explore how it has been working. As students in the Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation Clinic at Stanford Law School, we scraped the CCB’s data with several research questions in mind.

Within the first year of the CCB’s launch, the data revealed that few cases reached final determinations and over 70% of claims were dismissed. We were curious about why this was, and whether this still held true after a few years. Which creators filed claims with the CCB? Were there clear patterns in the effect of representation on case outcomes? What were the reasons claims were dismissed, and could creators use this information to prepare claims that are likely to succeed in the future? Guided by questions about who the CCB serves and why, we investigated cases in the CCB’s docket from its start in June 2022 through January 1, 2025. Our findings are summarized below.

Few Cases Reach Final Determinations

- Of more than 1,000 cases in CCB’s docket, only 18 cases, or 1.8%, reached a final determination. To reach this stage, a case must be properly filed, clear the CCB’s compliance review, meet service requirements, and of course, reach a determination on the merits of the case. Some cases are dismissed before this point for several reasons, which we will cover later.

- A number of repeat claimants reached final determinations in at least one of their claims. Julie Dermansky, Joe Hand Promotions, and Michelle Shocked have each filed more than 10 claims with the CCB and each has reached a final determination for at least one of their claims.

- Among final determinations where the claimant prevailed, the damages awarded ranged from $1,200 to $7,000.

- Claimants and respondents in cases that reached final determination varied and ranged from individuals to well-known corporations. Claimants also sought to enforce protections of several types of works, including songs, photographs, university assignments and paper prompts, novels, videos and more.

- It is unclear whether certain types of claims, claimants, or works are more likely to reach final determination than others. However, what is clear is that the chances of getting to this stage have been slim, even for those who are more experienced with the CCB’s process.

The Majority of Cases are Dismissed

- Dismissal is the modal outcome for cases filed with the CCB, though dismissal can occur at several stages in a proceeding. As these dismissals are most often without prejudice, parties can still re-file their claims after dismissal if they choose to.

- The most common reason for dismissal is failure to timely or properly amend a complaint. This happens when a complaint does not meet the CCB’s requirements during early screening. After claimants file their claims, the CCB reviews them (in a phase called “Compliance Review”) to surface issues. The CCB alerts claimants of these issues and asks claimants to amend their complaint within a given period of time to fix them. These issues vary, but include missing information in the claim, failure to pay fees, missing copyright registration (when required), use of the claims process against someone who does not reside in the US, or use of the CCB for claims the tribunal cannot preside over (e.g. contract disputes related to copyright licensing). Sometimes, parties did not file amended claims at all after being notified of issues, resulting in dismissal. In other cases, claimants did amend their claims, but those amended claims still did not pass compliance review after two rounds of amendments. If the amended claim still presents issues after the second opportunity to amend, the CCB will dismiss it.

- The second-most common reason for dismissal involves issues with providing service, including failure to file proof of service and ineffective service. While the CCB’s proceedings are relatively streamlined and simplified, rules of service come from a different authority: the respondent’s applicable state law. Service can be more difficult to navigate than other stages of a CCB proceeding for this reason, and the service rules can vary by state.

- Close behind is dismissal because the respondent opted out of the case. It may seem unsurprising that a respondent would choose to opt out of a case, however, claimants are also able to drop out which was the fourth common category of dismissal types. These trends in dismissals stayed relatively stable across 2022-2024. While it is not possible to tell why claimants request to dismiss their own cases, it may be the result of settlements the parties have reached outside the CCB or their choice to use federal courts to resolve the issue instead.

Demographics and Dismissals

- Effect of Representation. Most cases that were not dismissed involved a claimant and a respondent who were both not represented by counsel. It is not clear that claimants are more likely to be successful in reaching a final determination if they retain counsel.

- Status of Party. Of the cases that were dismissed, it was more likely that both parties were individuals. In general, the majority of claimants and the majority of respondents are individuals—significantly fewer are corporations, LLCs or other entities (e.g. nonprofits or government entities).

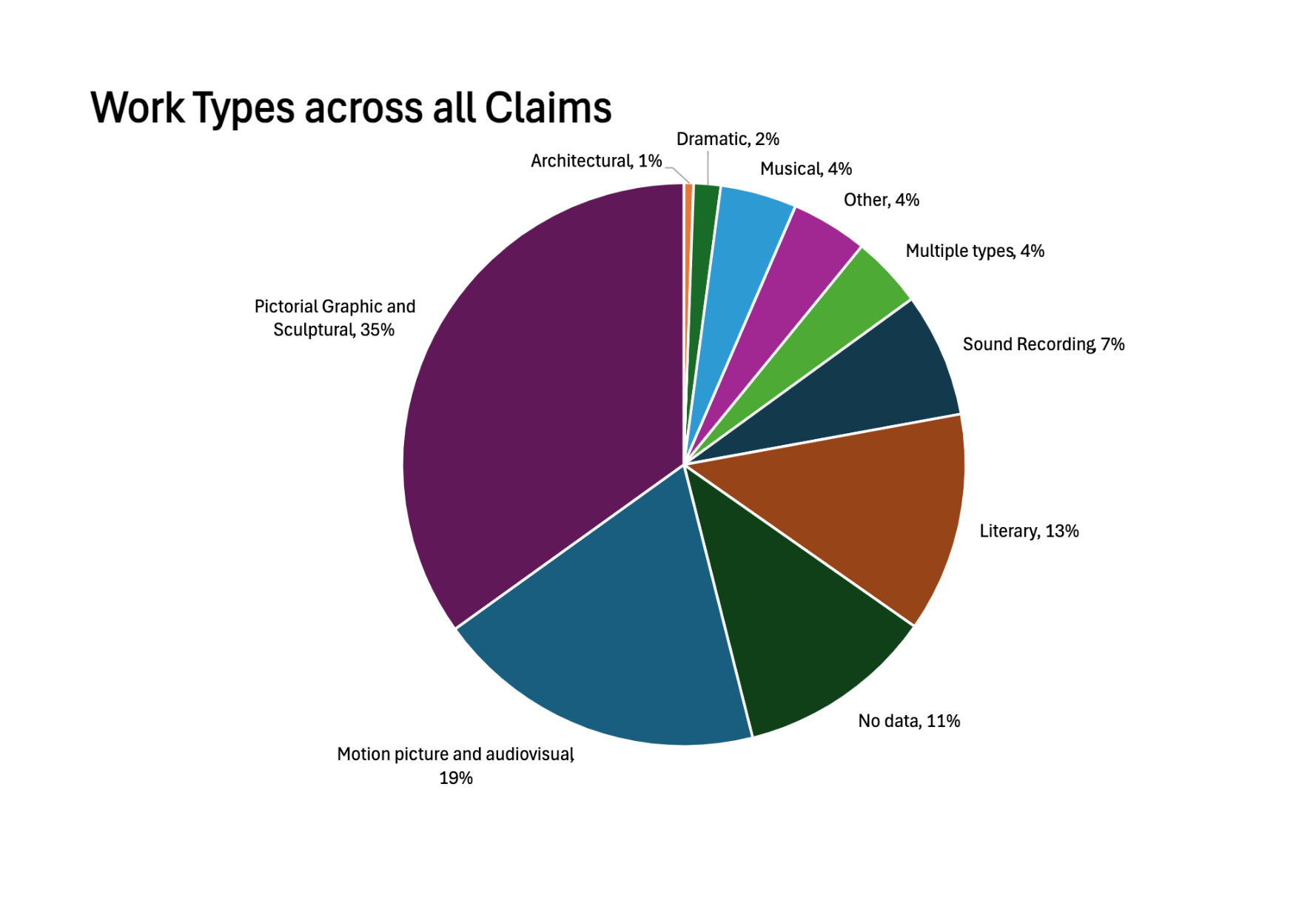

- Work Types. Of the cases that were dismissed, most claims involved pictorial graphic and sculptural works. The chart below shows the demographic breakdown of work types across claims that were dismissed. The highest number of dismissals involved claims for pictorial graphic and sculptural works. However, the percentage rate for dismissals of claims involving musical work types (94%) was higher.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

In general, claims covered a variety of work types, but the most common were pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. We generated this pie chart based on data from June 2022 (when the CCB began to accept claims) to January 1, 2025.

Claimants and Respondents

With the data that was collected, we were able to see where claimants were actually located, and we found that most domestic claimants were located in California. New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Florida also had a large number of claimants. Outside of the US, the top countries represented were the United Kingdom, Ukraine, Germany, and Canada.

Some parties appeared in front of the CCB as a claimant in one case and later again as a respondent in a different, unrelated case. There were some parties, for example, who were respondents in a claim in 2022, and then appeared as claimants in 2023 or 2024. There have been a handful of claimants who have brought more than 10 claims to the CCB in the past couple of years, and similarly there have been a handful of respondents involved in more than 10 cases in front of the CCB in the past couple of years.

A large number of these repeating respondents are platforms such as YouTube, Amazon, and Etsy. In these cases, the claimant was generally not represented by counsel, and every case against a content service provider was dismissed. Still, the fact that these claims were dismissed does not necessarily mean that the claimant was unsuccessful. Some claimants brought claims against a platform to have someone else’s infringing content, which was hosted on the platform, taken down. Claimants can only bring a claim against an online service provider if it loses its safe harbor under Section 512 of the Copyright Act. Online service providers gain a safe harbor by providing a platform for handling takedown notices and handling requests in a timely manner, as outlined by Section 512. If a claimant files a takedown notice with a platform for potentially infringing material on the platform, the alleged infringer can file a counter notice. The online service provider may choose to reinstate the content while waiting for the claimant to bring formal legal action. It is usually in these situations where a claimant brings an erroneous claim against the platform as opposed to the infringing author. The CCB has no obligation to a claimant who brings a misrepresentation claim against a platform if the platform still has safe harbor—the actual conflict is between the author of the infringing content and the claimant. In addition, even if the platform lost its safe harbor, it can still choose to opt out of the CCB proceeding.

Tracking Federal Legislation on Gig Work and Web3

There is plenty of turmoil to go around in Washington, DC these days. CCI is not immune to such turbulence. And at the same time, our work at the edge of arts, culture, safety nets and technology give us the visibility to see the opportunities embedded in the current moment. They do exist! For this reason, while CCI does not at present engage in policy and advocacy, we are tracking federal legislation that affects our priorities of individual and community self-determination. Below, I have highlighted four legislative items: two pertaining to gig worker safety nets (one that passed and one that is still pending) and two pertaining to cryptocurrency regulation (one that passed and one still pending), which may affect the many artists who use or engage with Web3 technologies to sell work and collectivize power.

GIG WORKER SAFETY NET LEGISLATION

PASSED: One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Bill. We were surprised to see the inclusion of so-called Trump Baby Bonds in the final legislation. It’s curious that a provision long pushed by progressives in the guaranteed income space was included in OBBBA, though in practice these baby bonds are far from the original vision. The “baby bonds” in the final bill are largely similar to retirement savings accounts (vs. some sort of child savings support) – but differ in that U.S. citizens with Social Security numbers born between 2025 and 2029 will get an investment of $1k by the Federal government in their accounts. The bill is scant on details, and it is likely that most accounts will be held by mainstream financial institutions and administered by the Treasury Dept.

PENDING: GOP Portable Benefits proposals. Sen Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and other members introduced several bills around independent workers. Cassidy’s attempts to separate benefits provision from the federal definition of “employee.” It would allow employers to provide benefits to their 1099 contractors without fear of federal prosecution for misclassification. A press release on the bills is here. Similar legislation has either been passed or is moving through statehouses in red and blue states (UT, TN and AL have enacted laws; AK, FL, NV and NJ have proposed laws). It is unlikely that any action will take place in this Congress, none is scheduled in the Senate as of now. The House Education Committee did markup a similar house version to the Scott Modern Worker Empowerment Act (essentially a classification text for federal law).

CRYPTO CURRENCY LEGISLATION:

PASSED: GENIUS Act, passed into law in July. It is an extremely specific bill that passed with bipartisan support. In essence, the bill established a federal framework for issuing and trading stablecoins (crypto assets usually pegged to the US dollar). This bill also allows traditional finance entities (banks, major retailers, and others) to enter the crypto market. The bill was relatively narrow in scope, leaving broader market structuring and overall regulation to the CLARITY Act, which has yet to pass both houses.

PENDING: CLARITY Act or the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act. The House passed its version in July. The Senate is currently working on its version, called RFIA (Responsible Financial Innovation Act). It is less likely to pass than the GENIUS Act, because it is far more comprehensive. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who was opposed to the GENIUS Act, has been far more vocal in her opposition to the more CLARITY Act in an effort to peel Senate Dems away from support of the bill. The bill would amend the Securities Act of 1933 to exempt most crypto assets from the definition of “securities” and thus regulation by the SEC. If passed, the CLARITY Act would constitute the first time in its history that the Securities Act would be amended to exempt (rather than include) an asset from the definition of a security, and could result in other securities industries seeking exemption from oversight. Leaders in Decentralized Finance or DeFi are quietly opposed to the bill. Seven Dems are needed to vote with Republicans on the Senate’s version of the bill to get it through the next step in the legislative process. Republicans hope to do so by the end of August, but the numbers are not in their favor.

Shaping Collective Futures: Co-Designing A New Social Safety Net for Artists and Gig Workers

A behind-the-scenes look at the Cookie Jar Collective convening, where artists, technologists, and policy leaders came together to reimagine savings as a shared resource and explore new models of digital public infrastructure.

Why a Convening?

On July 15, 2025, the Center for Cultural Innovation hosted an in-person co-design convening in Los Angeles, California titled “Shaping a Savings Benefit for Artists and Gig Workers.” The goal of the convening was to bring together a diverse group of stakeholders–including artists, technologists, and policy experts–to engage with an early concept for a technology-enabled system designed for artists and independent workers to pool their savings and collectively decide how and where to spend, loan or invest it. The project is informally called the Cookie Jar Collective.

Our team decided to host the co-design convening because, while we had a semi-clear conception of the tool, we still found ourselves bumping up against many key implementation questions. We had conducted thorough background research, engaged with artists in focus groups, and hosted a technology-focused co-design session at DWeb Camp ‘24, yet we still did not feel confident enough to start writing any code–perhaps because this project has highly ambitious goals.

Our main goals for this system is to help grow the financial security and social cohesion of independent workers. Not only that, but we hope that our system can inspire a shift in the way people relate to money–to see it less as individually-held resources and more as shared resource commons held in communities of trust and governed by mutualistic, cooperative, and solidarity-oriented agreements. The model is based on the concept of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs, sometimes called tandas or sou-sous) that have been present in communities of color in the U.S. and abroad for generations. We are building on that legacy of mutual aid with the Cookie Jar Collective. Our hope is that we can leverage new technology to scale this idea to a large number of freelancers.

Finally, we aim to demonstrate how U.S. policy makers can use our system to expand benefits for non-traditional (non-W2) workers, a growing share of the workforce who are excluded from a social safety net that only protects those engaged in traditional employment. We realized our ideal roadmap for this system would include it potentially being adopted by a state or local government as a “public option,” similar to state retirement funds like CalSavers that are available to freelancers on an opt-in basis.

These social, cultural, and policy change goals required us to engage early with a broad range of stakeholders, making the participatory model of co-design an ideal design step for this project. This is the Research to Impact Lab’s first incubation project, which means that we are testing different aspects of our technology incubation process and learning along the way. What level of participation is useful? How can we move quickly and keep learning along the way? We’re not a government, though we do intend this product for public good; and we certainly aren’t a tech start up, though we want to be able to innovate swiftly. As a result, we strive for a balance of participation somewhere in between democratic governments building public infrastructure and traditional technology startups building products for profit.

Building digital public infrastructure means not seeking profit but rather seeking positive effects of relationality, participation, social cohesion, diverse opportunities, mutual support and benefit, maintenance, and care.

Our Planning Process

The R2I Lab team engaged in an approximately 9-month process to prepare for and plan the co-design. We began with a selection process for a human-centered design firm partner with whom we would collaborate on the convening design and facilitation. Greater Good Studios (GGS) was ultimately chosen as our partners because of their prior experience working on technology that directly drives state-level policy change.

With GGS’s support, we proceeded with our participant selection process. It was crucial to our team to meet with each prospective invitee individually to connect with them on a personal level, hear about their work, practice explaining our concept directly to them, field any follow-up questions, and gauge their interest in collaborating on the project.

Once we had our twenty-two total participants confirmed, we worked on designing the agenda–again, with the help and guidance of GGS. The whole experience was intentionally designed, including a welcome dinner the night before the convening, in order to create a space for folks to meet and connect across their areas of expertise and interest. On the day, our agenda included three distinct segments: 1) introductions and weaving connections between participants, 2) building a shared understanding of the concept and fielding questions, and 3) collaboratively designing systems with different constraints in small, assigned groups. These segments were cushioned with meals (breakfast and lunch), breaks, and time for conversation and connections.

The Flow of the Agenda on the Day

The event transpired smoothly in that we remained on schedule with plenty of time for each program activity and suitable break time in between.

Each segment on the agenda flowed nicely into the next. Having each participant introduce themselves allowed other folks in the room to build bridges across domains of expertise yet trust in everyone’s values-alignment. Participants expressed the immense value in the diversity of perspectives present in the room including: technology builders from web3 and the decentralized web who recognize the importance of shared governance; leaders of existing tech-enabled mutualistic projects (i.e. Kola Nut Collaborative, Boston Ujima Project, Freelancer’s Union); career policy experts who focus specifically on benefits and safety nets for a changing workforce; Biden administration Department of Justice appointees as well the founding director of CalSavers, a public option retirement savings program; and of course artists who specialize in solidarity practices in their communities, leading cooperatives, collectives, and other mutualistic efforts either utilizing tech or in analog spaces.

In the second segment, we presented the most updated vision of our concept and invited participants to share reflections and ask clarifying questions. We told them, “Take our concept but hold it loosely.” This segment produced a lively Q&A where participants were able to massage the ideas presented, question assumptions based on their own work and experiences, and start to form their own internal vision of what the tool is, how it might work, and where it might be implemented. We were met with many of the same questions we, as a team, have been wrestling with. However, with these key questions in everyone’s mind, we were laying the groundwork for the final exercise–where we formed small groups to answer these questions given different sets of constraints.

Each small group was given one of the following scenarios for the concept: 1) subsidiarity/federated model, 2) platform cooperative, 3) public option, 4) VC-backed app, and 5) DAO/Web 3 version. Using these scenarios, the groups envisioned what the Cookie Jar Collective could look like and answered questions such as: “What is the role of technology?”, “How large are the shared funding pools?”, “What does shared governance look like?”, and more. During the share-outs from this exercise, heard five different manifestations of the concept–each making its own tradeoffs in order to conform to its given structure while accomplishing the project’s goals.

Our Takeaways and an Unexpected Surprise

The convening demonstrated that the problem we are trying to address–the lack of financial security / safety nets for artists and independent contractors–is deeply resonant and there is a hunger for solutions to this problem. Participants felt excited and inspired to be brought together to work with others on designing innovative, more community-driven and collectively-governed solutions to this problem.

- There seemed to be agreement that the solution is complex and therefore requires multi-disciplinary and cross-sectoral collaboration. Many participants expressed the positive value of gathering together in-person and with individuals from such diverse backgrounds and experiences. Many wished the convening could have been longer than just one day because of this complex nature of the system design. In a follow-up form, more than half of participants have expressed interest in continuing involvement in this design process–from technology development, pilot design, user research, partnership development, and more.

- There were elements from each of the 5 scenarios expanded upon at the convening that our team is interested in incorporating into our pilot. Therefore, rather than trying to come to consensus around one singular version of the Cookie Jar Collective, we are working on shaping a list of 2-3 versions around which we can design small pilots with groups of artists from CCI’s core constituency as well as adjacent partner communities.

- As for next steps, we will design and share our pilot program in the next couple of months and conduct outreach to prospective pilot participants and communities–including many of the co-design convening participants and their respective communities. We are also going to be hiring a founder to lead the development of the technology-enabled features of the tool.

- One unexpected surprise was how the success of this convening informed internal conversations within CCI about best practices for building out its relational infrastructure–processes for relationship-formation across multi-disciplinary, cross-sectoral groups to unlock potential future partnerships for our work but also for each participant and their specific projects.

Overall, the convening allowed our team to share the in-progress development of the Cookie Jar Collective concept and receive extremely constructive feedback. We believe that doing so early in the project’s design is essential not only for effective design but also for generating buy-in from the public, private, and civil society sectors. Continuing to build in participatory ways, we believe, will help ensure we don’t repeat past mistakes and that we build something that stands to weather changing economic and political conditions–as good digital public infrastructure should.

We look forward to the next phase of this work!

Read the Co-Design Convening Summary HERE

Read our Concept Brief HERE

CCI at DWeb Camp 2024

CCI at DWeb Camp 2024

Reflections on our Co-Design and path forward

Systemic change to legitimize gig work won't come from band-aid solutions.

Research to Impact Lab's Senior Program Associate, Jennelyn Tumalad Bailon, and Enterprise Development Consultant, Val Elefante, facilitated a co-design for our gig worker savings club incubation project, currently known as "Cookie Jar Collective."

We welcomed 27 participants interested in helping us build a product that could facilitate shared accountability, community, and collective power centered on growing savings for gig workers.

Participants heard an overview of the purpose and journey CCI has taken to reach this point. They also spent time brainstorming and drawing different aspects of the product ranging from governance, UX design, and tech stack.

Watch the in-depth overview of our presentation, key takeaways, and next steps for this project in the video below.